The Basics

I can’t stress enough about how important it is to bring a first aid kit (FAK) with you on any adventure you go on. Whether it is a short day hike or a multi-day backpacking excursion; I strongly urge everyone that ventures into the Backcountry to have some form of first aid to treat and prevent further injuries or infections. This blog post will be a guide for putting together/customizing an adequate FAK as well as some ways to treat common injuries and ailments that occur while partaking in outdoor activities.

How to Build Your FAK

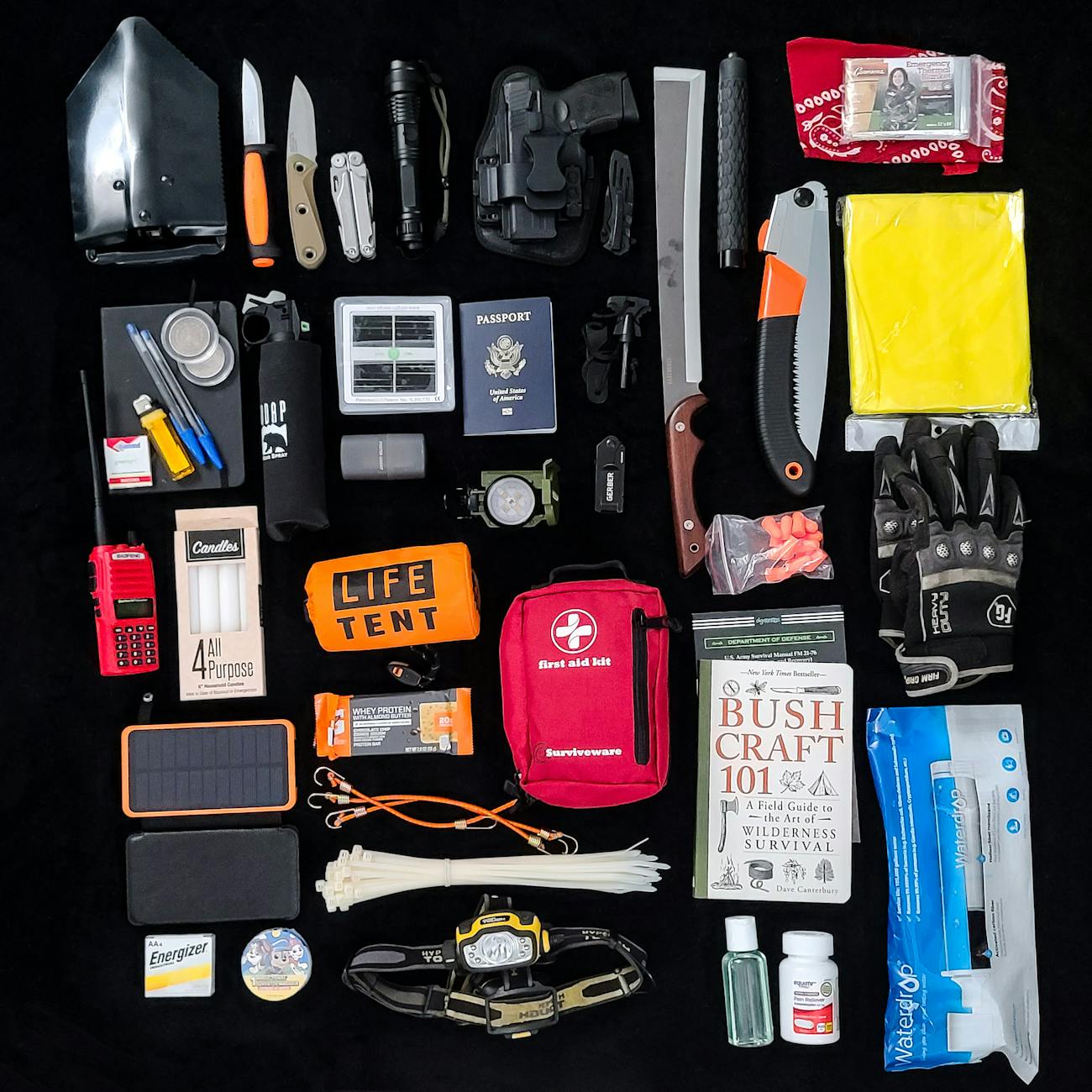

Every kit should have basic first aid gear at a minimum. For example, you should have more than enough bandaids, some form of antibiotic cream or ointment, a compass and map of the area you’re exploring, a pair of tweezers, gauze for bleeding control, a tourniquet, and some form of over the counter pain reliever/fever reducer.

Digging a little deeper, if you have a known allergy to anything that may be in the vicinity, you should add your epipen to your FAK. Another piece of vital gear that I add to my FAK is benadryl (antihistamine). This could be a game changer if you have an adverse reaction to anything while miles away from the nearest medical resource. You should also incorporate at least 3 days of any daily Rx meds, just in case you are lost/stranded.

Other miscellaneous items I like to incorporate into my FAK are splints (multiple sizes for certain injuries), anti nausea tablets, a basic fire starting kit, rescue whistle, hand sanitizer, emergency bivy, headlamp with extra batteries, water filtration device, and lidocaine wipes for insect stings/bites.

I should also mention that you should become very familiar with how to use the items in your FAK. It goes without saying that your FAK is useless unless you know how your gear works. If you’re unfamiliar with a certain item, research it! Knowledge is power, and it could save a life.

Customizing your FAK

Customizing your FAK to meet the demands of your adventure is crucial. As noted earlier, a short day hike may only require a kit that has only bandaids, antibiotic ointment, and OTC pain relievers for sore joints.

If you’re planning a multi-day backpacking trip into the Backcountry, you need to be more precise in how you build your FAK. The golden rule for any multi-day adventure is to be prepared for 72 hours of self reliance. This means that you should pack enough emergency supplies, food and water to last up to 3 days. The following section will touch on some common injuries and ailments that occur in the wilderness.

Common Injuries/Ailments in the backcountry

When you’re out exploring in wild areas, anything can happen. Mother Nature is unforgiving if you aren’t prepared. Some common injuries and ailments that may occur are: minor sprains/strains, bone fractures/dislocations, minor lacerations, life threatening hemorrhaging, head injuries, dehydration, GI issues, allergic reactions, etc.

Any of the aforementioned complications could happen to anyone on any given day. Imagine being on day 4 of a 7 day trek and you slip on loose rock in a scree field; You sustain a broken leg with uncontrolled bleeding. The closest medical resource is 30 miles away. Are you prepared to handle this situation and make it back to civilization before it’s too late?

Dehydration and allergic reactions are common ailments that can put a damper on your “epic adventure”. Dehydration, if not addressed in a reasonable time, can be lethal. You can only survive 3 days without any water intake. It could be less if you’re in an environment with extreme heat and humidity or frigid temps. If your body is in a dehydrated state for long periods of time, you become confused and you organs shut down, eventually leading up to death.

Allergic reactions are another concern while exploring the great outdoors. It could be as little as an irritating itch from poison ivy to a life threatening anaphylactic reaction from a bee sting. There’s no such thing as being “overly prepared” when it comes to dealing with the elements that Mother Nature throws at us.

How do we treat these emergencies in the backcountry? Glad you asked! The following section will give you a basic idea of how to treat and care for common injuries/ailments in austere environments.

Treatment/Care Plans for Injuries/Ailments in the Backcountry

Remember that handy dandy first aid kit that we discussed earlier? Now is your time to utilize it! As I mentioned in the How to Build Your FAK section, get to know your gear before an actual emergency happens. If you don’t know how your gear works, then you’re up sh*t creek without a paddle. Let’s explore some effective methods to handle emergencies that could happen in the backcountry.

Traumatic Injuries:

Traumatic injuries in the wilderness can be as little as a little scrape from a thorn, to as serious as plummeting 100 feet down a sheer drop-off. According to Backpacker.com, “About one-third of backcountry injuries involve the head or spine, which can include concussions.” These injuries are critical and could potentially result in paralysis or worse if not addressed urgently. The best treatment for these injuries in the wilderness is evacuating the patient and getting them to definitive care ASAP.

Sprains/Strains: If anyone in your group (including yourself) endures a sprain or strain, the best is to rest (if possible). Apply ice or dip the injured area in cold water for approximately 30 minutes to help reduce swelling. Take some Ibuprofen to help alleviate the pain and swelling. Use an ACE bandage to wrap the injury to help immobilize and reduce swelling. An easy mnemonic to remember for these types of injuries is RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation).

Joint dislocations/Broken bones: These can be more serious injuries that could be sustained in the wilderness. These injuries are considerably more painful and result in a higher priority treatment plan. Broken bones could potentially cause internal injuries that are difficult to address until later stages.

An invaluable tool to use for these injuries is the SAM Splint. It’s a compact splint that will be easy to mold around the injured region to immobilize it. Correctly size the splint to adequately immobilize the dislocated joint or broken bone and secure the splint by wrapping above and below the injury. After securing the splint, check for a pulse on the injured area (i.e. radial pulse in wrist or pedal pulse on top of the foot). It is crucial not to cut off circulation while immobilizing an injury.

If you don’t have a SAM Splint, you can simply use 2 branches that are appropriately sized and secure it with gauze, cordage or some form of cloth that adequately secures the branches to the injury site. Once you immobilize the injury, check for pulses.

Bleeding and Wound Care:

If you or a group member sustains an injury that results in bleeding or significant wound, you’ll want to promptly control the bleeding. There are multiple levels of severity when it comes to injuries that result in bleeding. These injuries can range from a minor cut that requires only a bandaid to a life-threatening arterial bleed that requires a tourniquet and air-evac by helicopter to the nearest trauma facility. Let’s dive deeper into recognizing, prioritizing and treating different levels of bleeding.

Cuts/Scrapes: These minor injuries are typically low priority. Simply wash the affected area with soap and water and apply a bandage or sterile dressing to prevent infection.

Lacerations: Enduring a laceration in the backcountry is a higher priority injury. Lacerations will bleed more than a minor cut. They present as dark red blood that can ooze or bleed profusely (depending on the severity of the laceration). The best treatment for this type of injury is direct pressure with gauze or form of cloth. Direct pressure is the most effective method to control bleeding from a laceration.

Arterial Bleeds: This is the highest priority when it comes to bleeding severity. Arterial bleeding presents as bright red blood that “spurts” from the injury site. Immediately apply direct pressure to the injury with plenty of gauze. If the bleeding doesn’t stop, this is where you will apply your tourniquet. Place the tourniquet approximately 2-3 inches above the wound. Tighten the tourniquet until you notice that the bleeding has stopped. Once the bleeding has stopped, secure the tourniquet as indicated.

Once the tourniquet is in place, you must never remove it. It will be extremely uncomfortable, but it is better than the alternative. This is the only situation that you do not have to ensure there is a pulse in the injured area. Immediately evacuate patient and have them taken to the closest trauma facility.

Miscellaneous Injuries: Some other injuries that could occur are burns, insect stings, and animal bites. To avoid sustaining a burn injury, use caution while cooking with hot surfaces and be smart around the campfire. Insect stings and animal bites should be cleaned thoroughly with soap and water. Apply antibiotic ointment/cream to wound if not too severe. Wrap injury in sterile dressing to prevent infection. Insect stingers should be removed with a flat, rigid surface (credit card). Removing a stinger with tweezers can squeeze more venom into the site, causing further complications.

If you or a group member have an open wound while on an adventure, it is imperative to immediately clean the site with clean water and soap. If you don’t have soap, irrigate the wound with copious amounts of clean water. My go-to technique for irrigation is using a syringe; Simply draw up your clean water and firmly squeeze the water onto the wound. Once you’ve cleaned the wound, apply an antibiotic cream/ointment (i.e. Neosporin) and cover the wound in a sterile dressing. This will prevent potential infection until you are able to further care for the wound in a cleaner environment.

You should keep the wound covered for as long as possible. Studies have shown that keeping the wound covered for several days improves recovery and limits scar tissue development. Depending on how severe the wound is, you should change out the dressing and reapply antibiotic cream daily. You may need to change it multiple times a day if you notice blood seeping through or dressing obviously needs to be changed.

Backcountry Ailments/Illness

We briefly touched on how common dehydration and allergic reaction emergencies occur in the wilderness and how detrimental those can be if not addressed promptly. Now, we will discuss how to treat these conditions and how to prevent further complications.

Dehydration: This is, by far, the most common ailment that pops up during outdoor activities. It is imperative to make sure that you pack more than enough water for your adventure. There have been numerous occasions where I thought that I packed a sufficient amount of water for my day hike. Boy, was I wrong. The rule that I now follow is to pack enough water to consume at least 1 liter of water per hour. So if you plan a hike that is 3 hours long, you’ll want to pack 3 liters of water (at a minimum). If hiking in higher elevations or more extreme weather, you’ll want to pack more.

Being in a dehydrated state for a prolonged period of time is detrimental to your body and will send you into a world of hurt if you’re miles away from civilization. I never go on a hike without carrying a water filtration device. This will save your life if you do run out of water. You can also carry iodine tabs to disinfect water sources. Another tried and true method is boiling water. This may not be ideal if you’re on a day hike. But if you’re on a multi-day trek and camping in the backcountry, this is one of the most efficient methods to maintain hydration.

Allergic Reaction/Anaphylaxis: Allergic and anaphylactic reactions aren’t as common as dehydration, but they are just as dangerous and have a much quicker onset. Let’s go over what to look for and how to treat these conditions.

An allergic reaction typically presents with hives, itchy skin, swelling of a body part, etc. Whip out that FAK and find some Benadryl (unless you’re allergic to this). Benadryl is an antihistamine and works wonders to treat symptoms of allergic reactions. You may also have some form a calamine lotion, which will soothe itchy skin from a poisonous plant. For seasonal allergies, a simple OTC allergy med should be sufficient to keep your trip enjoyable.

Anaphylactic reactions, however, are much more lethal. This is a life threatening event. These are typically brought on by insect stings or nut allergies. The number 1 tool you want in your FAK to treat this is an EpiPen, as it is the only thing that will correct an anaphylactic reaction.

Signs and symptoms are facial swelling, itchy throat, difficulty swallowing, and shortness of breath. If you or a group member fall victim to anaphylaxis while in the backcountry, immediately take the EpiPen and inject it into the outer thigh muscle. Hold EpiPen in place for at least 10 seconds to ensure all the medicine is injected.

If an insect sting is the result of anaphylaxis, be sure to find a flat, rigid surface to remove the stinger. This could be a credit card, a playing card, or the sharp edge of your knife (use with caution to avoid further injury). Using tweezers or trying to pinch the stinger with fingers can squeeze more venom into the body. This can potentially cause another anaphylactic reaction.

Once you treat the reaction with an EpiPen and remove the source that resulted in anaphylaxis, immediately call 911 and evacuate the patient. Getting them to the hospital quickly can be the difference between life or death.

Wrapping it Up:

There are a multitude of traumatic/medical emergencies that can occur in the backcountry. Far too many to squeeze in a single post. We can touch on those subjects at another time, or feel free to shoot me a message. I will be happy to answer any questions regarding traumatic/medical emergencies in the backcountry.

So, before you venture out on your next day hike or expedition, remember to adequately stock your first aid kit. The last thing that you want is to be ill prepared in the wilderness.